Painting an artist in a studio

By Winsome Spiller May 2016

Some time ago Richard Collins asked me if I would sit for a painting of myself in my art studio. So over three or four sessions, I sat very silently and still for perhaps twenty minutes at a time, over an hour or so. Surreptitiously, I also observed Richard at his work. The experience led me to reflect on the act of painting from life. Seeing the painting as I do, through the eyes of the ‘artist subject’, also led me to consider how its construction and painterly qualities might say something about what I, and my studio, might be like.

For the portrait sittings, I wore my painting clothes, drab and not very flattering, and didn’t rearrange my studio from its usual state. A rectangular and rather spartan space, it was one of many studios in a cavernous converted industrial building. It had one long wall of strange orange terra cotta blocks, above which ranged a line of above eye-‐level windows. The remaining walls were partitions – the long one mainly of ancient flaking cream-‐painted corrugated iron.

Furniture was minimal -‐ clear plastic filing drawers and a couple of brush holders and mugs stood on my cheap work table. I had stuck various small objects and a thermometer on the wall above. I kept a rather sagging pillow draped over my aluminium folding stepladder to make a spare seat.

Paintings covered every inch of available walls: works in progress on nailed-‐up large unstretched canvasses and sheets of clear plastic, and rows of finished works on stretchers leaning faces-‐to-‐ the-‐walls, like some inverted sidewalk exhibition. I saw my studio as a factory for making art, in contrast to more domestic spaces for living or relaxing in. A silent rain of constant dust dissuaded me from decorating it with personal possessions or valuable art books.

The light was bright, and probably warm-‐toned: from a high but reflective ceiling, highlight windows uncurtained from sunlight, the strange orange wall and a warm grey floor. In contrast, most of the works in the studio were blue, apart from an acidic green and yellow underpainted canvas I was working on at the time.

Situating the painter, situating the subject

As I watched, Richard seemed to size up his surroundings, eventually placing the easel near a corner, about two metres away, so his view of the studio was diagonal across the long axis of the room, and I would be seen half side-‐on, not looking directly at him. Perhaps he moved the stepladder with the white pillow a few inches. He marked the position of the easel and the position of my stool and the stepladder on the floor. I sat: he stood, seeing me from quite a lot higher up.

Artists painting in their own studios can choose and arrange objects precisely to convey some sort of story, or insight into the sitter’s occupation, or character. But the visiting artist must set up in someone else’s space, without the luxury of arranging the mis en scene to suit their own purpose. Indeed, they voluntarily set themselves the task of using whatever they find as their ingredients. I see this as somewhat akin to plein air painting (an important element of Richard’s art practice).

As a further constraint, Richard did not have the luxury of unlimited time., but rather had to fit only a few sessions into my schedule. Yet in the hands of an experienced artist, this may be an asset -‐ in the same way that short poses in life drawing often generate more expressive and elegant constructions than those lost in more labored long poses.

The compositions in these paintings of figures in interiors reveal Collins’ expertise at placing himself (the machine for viewing) in relation to the sitter and space, and in choosing which elements and objects to deal with. This reflects his long artistic engagement with the human form, and with interiors.

Richard has made an abiding study of interior spaces. Rooms, studios, corners, furniture, frames of doorways or windows, staircases, drapery, the abstract shapes constructing interior spaces,

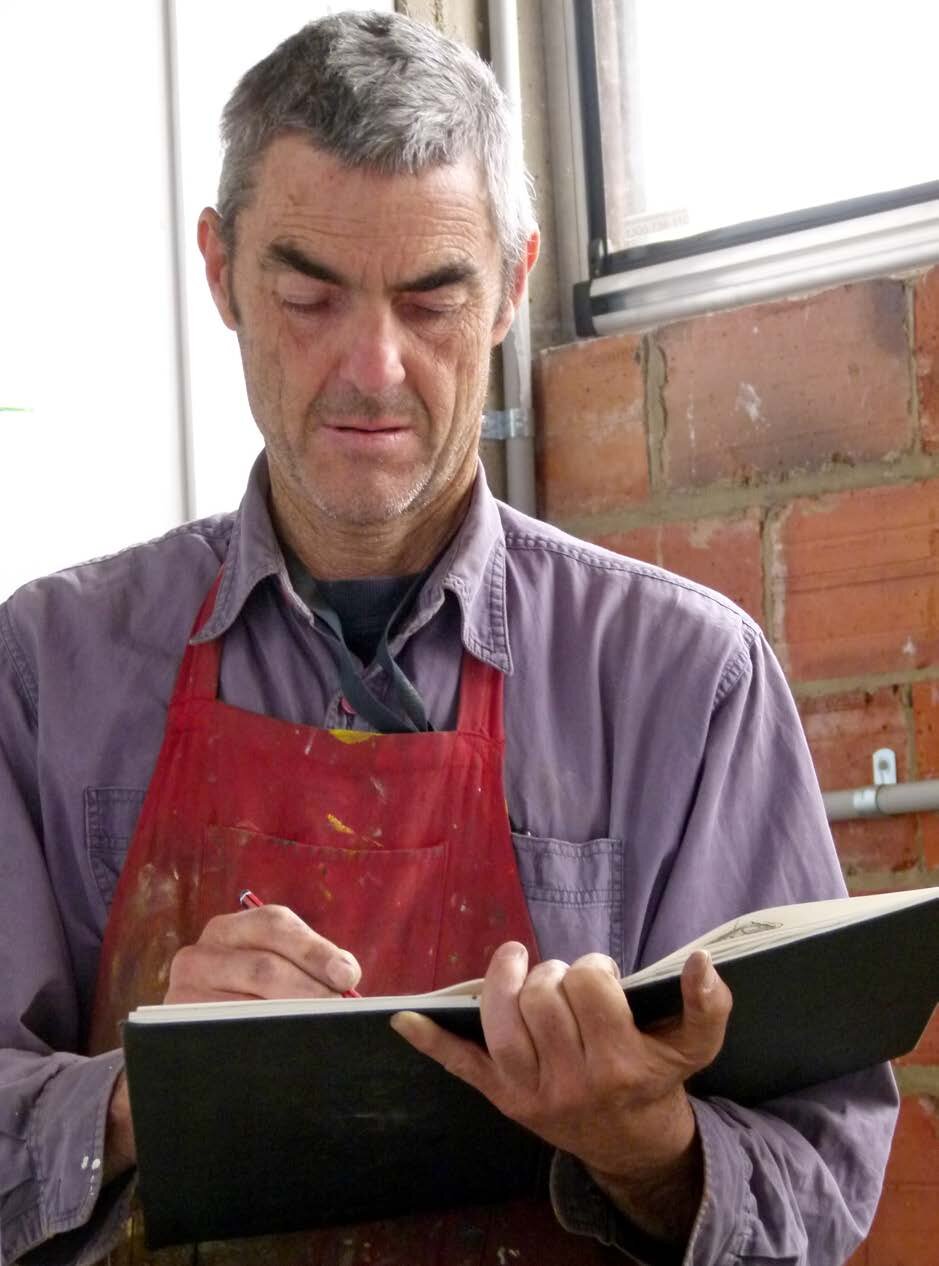

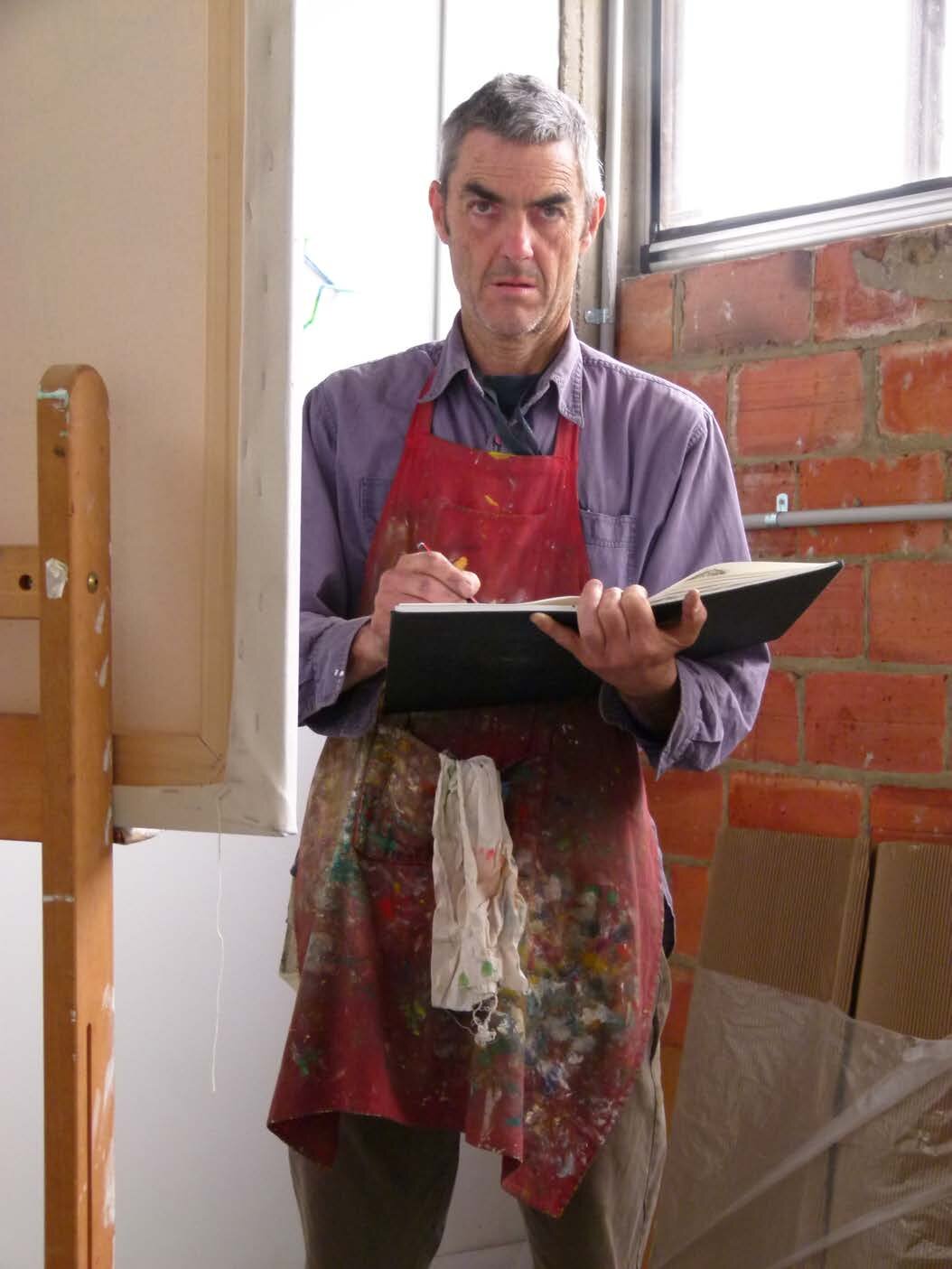

the fall of light and effects of colour. His images are always underpinned by strong abstract compositions and carefully considered colour palettes. His tacit knowledge of how people sit, stand, lie, recline, ponder, walk, move and otherwise arrange their bodies has been honed by from many years of observation, a career in drawing, training and practice in theatre, and an expansive knowledge about artists through history. He continuously sketches as he goes about his art life – people on trains, walking along streets, assuming strange poses, relaxing, reading.

Moving to look and paint

During the three or four sessions Richard made some sketches and then painted with complete concentration. I could see him while painting, moving backwards and forwards, squinting, peering, holding up fingers measuring proportions, disappearing behind the easel and reappearing, observing the painting from far and near. Occasionally resting from the sustained effort of just looking: eyes downcast, taking a breather.

I was watching how, to create the still image that is a painting, the artist engages in a cycle of looking, moving and gesturing involving their whole body. Looking at the sitter, looking at the palette, at the colours mixing on the palette or on the canvas, gesturing with the brush, looking at the sort of brushstroke being painted, looking at the mark the brush has made, looking back at the sitter, looking at the detail in the context of the whole painting. Moving back and looking at the painting in relation to the whole scene. Maybe moving closer to the sitter or object to check detail in the light or colour. Looking at the canvas from a distance to see how it reads from further away as well as close up, how it might draw the viewer to see it from far away and then move closer.

The painting

As I look at the painting that resulted from these studio sessions, I see a central figure sitting in a firm, dumpy triangular shape of solid, dark tones, brightly lit. Gazing diagonally out of the picture frame, her expression seems to be one of abstract thought, not related to the space the figure inhabits, but more to an interior world not seen at all. The painting frame crops the space, and lines lead one’s view outwards creating a space for imagining what else might be in the room.

Brushstrokes and colours convey light and transparency, ephemeral materials: transitional surroundings, in contrast to the solid and stable figure).

A satisfying circle of interesting marks and forms leads my eye round the canvas. A sweep of blues from the right foreground, past the figure and out of the top left of the frame. At the top right, from behind the figure’s head, a rising stack of lines and tones with some punctuations from small objects. Just off-‐centre of the composition, the white pillow echoes the sitter’s pose in a slumping crouch like some weird companion. The warm grey floor provides a tonal balance and restful negative space.

As the works shown are either unfinished or turned face about, their colours and shapes seem to operate as abstract forms rather than as clues to claim insight into the sitter’s possible character.

The painting as time machine

Now that I have moved out of that studio, I realise that the painting has become a sort of time machine, preserving a both the painter’s impressions, and the sitter’s memories of that particular time and that particular place. In fact, this is the only painted record of those painting clothes, that arrangement of furniture, that time, in that place, that light, -‐ those things that will never return in exactly the same way.

Made in paint. Thank you Richard.